<<Interesting facts regarding this history: these Bhils were demanding an end to their exploitation by the Brits and local princes; their leader??was an outcaste Banjara gypsy guru: the central symbol of their Nature-worshiping “Bhagat” belief system is the dhuni, a cleft earthen hearth??representing the yoni (vulva) of Shakti, goddess of the energies of the living??Earth; outside Gujarat & Rajasthan this atrocity has been??totally??ignored.>>

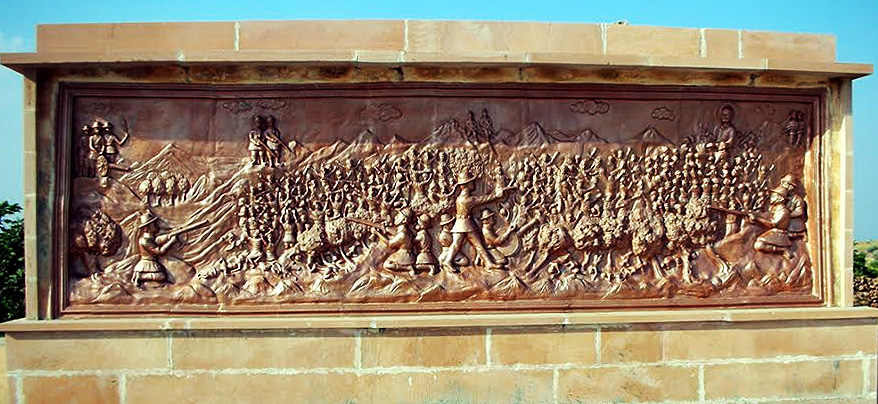

The Massacre on Mangadh Hill

Gujarat has a Jallianwala Bagh too. On November 17, 1913, the British gunned down more than 1,500 Bhils on Mangadh Hill, on the border between Rajasthan and Gujarat. INDIA TODAY speaks to the descendants of those killed.

In the hills and valleys of the Aravalli ranges on the Gujarat-Rajasthan border lies buried a brutal tribal massacre committed nearly a century ago, on November 17, 1913. Oral history, academic research and an india today investigation spread across several villages of Bhils in the Banswara-Panchmahal-Dungarpur region pieces together a little-known tragedy, one that echoes the massacre at Jallianwala Bagh, Punjab, on April 13, 1919, when British forces under the command of Brigadier-General Reginald E.H. Dyer shot dead 379 people, though nationalist historiography puts the number at over 1,000 people. Oral tradition of the Bhils has it that as many as 1,500 followers of social reformer Govind Guru, a banjara (Gypsy) from Vedsa village near Dungarpur in Rajasthan, were felled on Mangadh Hill by British forces. The guru had launched a movement called “Bhagat movement” in the late 19th century among Bhil tribes, which aimed to ’emancipate’ them by prescribing, among other things, adherence to vegetarianism and abstinence from all kinds of intoxicants. Inspired by the guru, the Bhils then rose against oppressive policies of the British and forced farm labour imposed by the local princely rulers of Banswara, Santrampur, Dungarpur and Kushalgarh.

Virji Soma Parghi, 86, Village Khuta Tikma, Banswara. His father,Soma Parghi, was one of the survivors of the Mangadh massacre.

Present-day descendants of both survivors and victims of the massacre have kept alive an oral tradition that recounts events on that fateful day. Magan Hira Parghi’s grandfather, Dharji, was among those killed. “My father, Hira, who died a decade ago, used to say that the firing started after British negotiators failed to convince Bhils to vacate the hill they had assembled on. The relentless firing was halted by a British officer only after he saw a Bhil child trying to suckle his dead mother,”says the 75-year-old from Amalia village in Banswara district of Rajasthan. Virji Parghi, 86, of Khuta Tikma village, also in Banswara, says his father, Soma, who survived the 1913 tragedy and died in 2000 at the age of 110, would recount to him that the British placed ‘canon-like guns’ on donkeys and made them swivel in circles while firing so that more people could get killed.

Magan Hira Parghi, 75 Village Amalia, Banswara; His grandfather Dharji was killed in the massacre.

Soma managed to escape and hid in a cave for days before returning home. “He said hundreds fell to bullets and several died trying to escape as they slipped down the hill,” says Virji. Gala Kachra, the grandfather of Bhanji Rangji Garasia, 58, also fell to a British bullet. “My father, Rangji, was only 11 when it happened. Before his death in 1991, he would often narrate that around 1,500 Bhils died that day,” says Bhanji, a resident of Bhongapura village in Banswara. Fellow villager Matha Jithra Garasia, 69, lost his grandfather Var Singh Garasia and his aunt in the massacre. “The killings created such a scare that Bhils stopped going to Mangadh for several decades after Independence,”says Matha.

The Government should sanction funds to conduct extensive research not only on Mangadh, but on the suppression of similar tribal uprisings against colonial rule.??Why be so step-motherly to the Jallianwala Baghs of the tribals?, says Arun Vaghela, historian at Guarat University. Lalshankar Parghi, 66, a Bhil farmer of Temerva village near Banswara, has been going from village to village collecting evidence on the gory episode. His grandfather, Tiha, an aide of Govind Guru, was also killed in the massacre. Tiha had played a key role in establishing village-level units of the Samph Sabha, a socio-religious organisation formed by the guru to strengthen his Bhagat movement. Lalshankar has so far collated oral accounts from over 250 families whose relatives died on Mangadh Hill. Tiha’s body was brought to the village by six Bhils who survived and it was cremated in an adjoining jungle. Lalshankar’s father Pongar later built a memorial at the spot and named it ‘Jagmandir Sat Ka Chopda’ (Jagmandir, the place of true history).

Followers of Govind Guru perform a ritual at a shrine on Mangadh hill.

Historical research backs the Bhil oral tradition. Arun Vaghela, 43, who teaches history at Gujarat University, says Govind Guru started his movement among Bhils in the early 1890s. The movement had, as its religious centrepiece, the concept of a fire god, which required his followers to raise sacred hearths in front of which Bhils pray while performing the purifying havan called dhuni. In 1903, the guru set up his main dhuni on Mangadh Hill. Mobilised by him, the Bhils placed a charter of 33 demands before the British by 1910 primarily relating to forced labour, high tax imposed on Bhils and harassment of the guru’s followers by the British and rulers of princely states. “The Bhil struggle for justice under Govind Guru took a serious turn after the British and local rulers refused to accept the demands and tried to break the Bhagat movement,” says Lalshankar.Sakjibhai Damor, 62, of Garadu village in Panchmahal district of Gujarat, lost his grand-uncle Vikabhai Damor, an associate of the guru for over a decade, in the massacre. “My father Gendarbhai used to tell me that thousands of Bhils had taken control of Mangadh Hill a month before the massacre vowing to declare freedom from British rule following rejection of their major demands, especially that of ending the system of ‘bet begaar’ (unpaid forced labour). A final offer by the British administration to give Bhil farm labourers Rs 1.25 per plough per year was rejected outright by the Bhils,” he says. Sakjibhai also recalls his father reciting to him Bhil songs of defiance against the British, one of which went thus: “O’ Bhuretia nai manu re, nai manu (O’ Britishers, we won’t bow before thee).

Bhanji Rangji Garasia, 58 Village Bhongapura, Banswara. His father Rangji saw Bhanji’s grandfather Gala Kachra being killed.

Vaghela says the immediate provocation for the British was an attack on a police station of the then Santrampur state near Mangadh by the guru’s second-in command Punja Dhirji Parghi and his supporters in which an inspector, Gulmohammed, was killed. The incident and simultaneous uprisings by Govind Guru’s followers in the neighbouring princely states of Banswara, Santrampur, Dungarpur and Kushalgarh convinced the British and the local rulers that the movement needed to be quelled. An ultimatum was given to Bhils to vacate Mangadh by November 15, 1913. They refused.”The Bhils turned Mangadh Hill into a fortress, assembling country-made guns and swords,” says Lalshankar. “They took on the British forces believing Govind Guru’s spiritual powers would turn the bullets into wasps,” says Bhanji Rangji Garasia. The combined forces of the British, comprising the Mewar Bhil Corps and the police forces of the rulers of princely states led by three British officers, surrounded Mangadh and started firing in the air to scare the Bhils away, and finally perpetrated the massacre.

Quoting archival records, a book recently published by the Gujarat Forest Department titled Govind Guru, The Chief Actor of the Mangadh Revolution states: “Machine guns and canons used in the attack were loaded on donkeys and mules and brought to Mangadh Hill and neighbouring peaks under the command of British officers Major S. Bailey and Captain E. Stoiley.” Principal Secretary S.K. Nanda, who organised the research for the book, says, “We involved officials to historians and amateur researchers to put the booklet together.”

The British political agent of the area, R.E. Hamilton, also played a key role in mounting the attack. “Several Bhils were killed and wounded and about 900 captured alive after they were fired upon following their refusal to clear the Mangadh Hill,” scholar Rima Hooja of the University of Minnesota, US, says in her book A History of Rajasthan from a report dated February 14, 1914 by R.P. Barrow, the then commissioner of the Northern Division.

Govind Guru was captured, tried and sentenced to life imprisonment. Owing to his popularity and good conduct in jail, he was released from Hyderabad Jail in 1919 but banned from entering many of the princely states where he had a following. He settled down in Kamboi near Limbdi in Gujarat and died in 1931. Even today, his followers come to Kamboi to pay homage at the Govind Guru Samadhi Mandir. Punja Dhirji, his aide, was sentenced to life imprisonment and despatched to the Cellular Jail in the Andamans. He died years after he had served out his sentence.

Official records cited by scholars such as Hooja and Vaghela bear out the rendering of local oral traditions, be it the mounting of canons on donkeys cited by Bhil villager Virji Parghi or the account of Bhils taking control of Mangadh Hill by Sakjibhai Damor.

The legend of Govind Guru and Mangadh massacre is etched in the memory of the Bhils. Yet for all their remembrances, the remoteness of the tribal belt of Banswara-Panchmahal straddling Rajasthan and Gujarat has consigned the monumental tragedy to an obscure footnote in India’s struggle for Independence. As Vaghela says: “The Government should sanction funds to conduct extensive research not only on the Mangadh massacre but on the suppression of similar tribal uprisings against colonial rule. Why be so step-motherly to the Jallianwala Baghs of the tribals?”

Incidentally, it was an india today investigation which had in 1997 brought to light another massacre of 1,200 tribals at Pal-Chitaria near Vijaynagar in north Gujarat by the British in 1922.

However, hope floats. The Gujarat government said on July 31 that it would commemorate the centenary year of the tribals’ freedom struggle against the British in 2013. Chief MinisterNarendra Modi also honoured Govind Guru’s grandson Man Singh while inaugurating a botanical garden named after the social reformer on Mangadh Hill. The July 31 event was attended by more than 80,000 Bhils. The tragic Mangadh massacre may finally get the attention it deserves.